I knew I could never walk the Haute Route (HRP) – too high, too technical, and above all I would need to carry a tent and all the extra kit that implies. But then, in the dog days of February, I came across TransPyr, a guide which claimed a tent wasn’t necessary. I looked at other guides to the Pyrenean Haute Route.

- Le Trek des Pyrénées by Céline and Sébastian Dupont

- Pyrenean Haute Route by Ton Joosten

- Souvenirs d’un Pyrénéiste by Georges Véron (account of his 1968 reconnaissance, out of print)

Each one proposes a different trek. The walk, it seems, is not a itinerary at all, more of an idea!

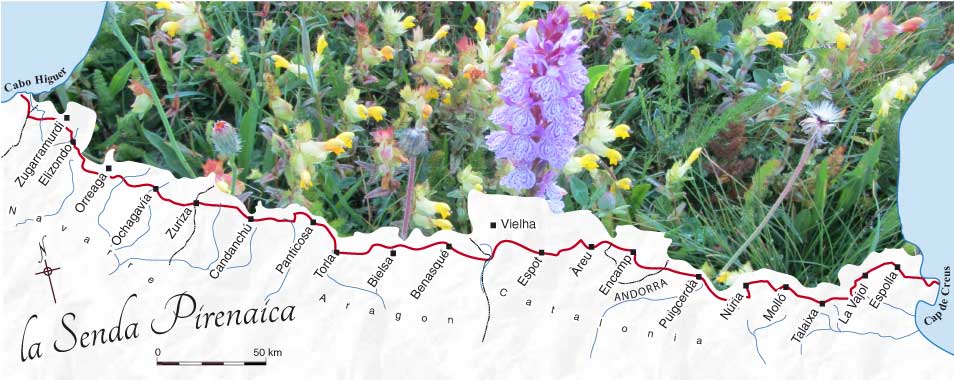

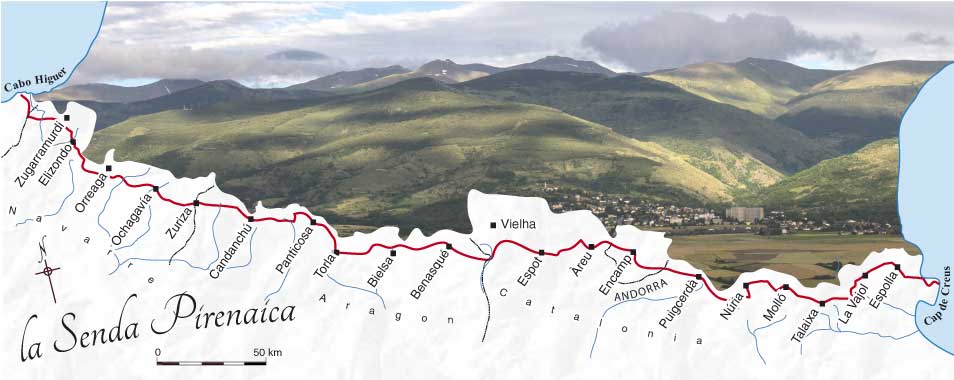

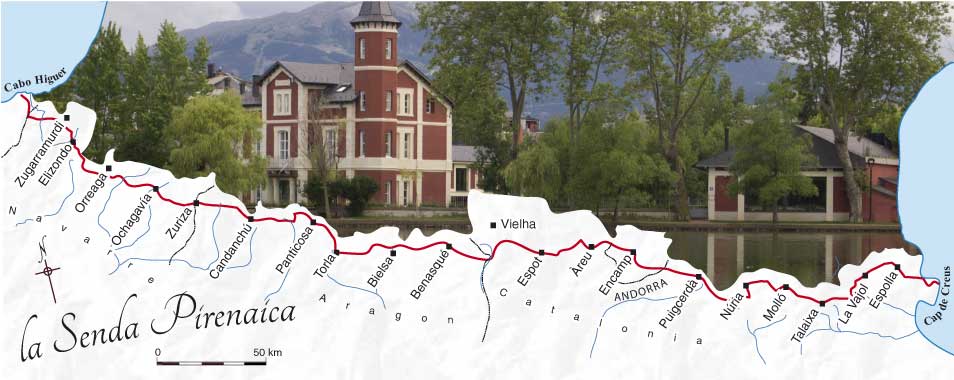

Conceived by Georges Véron as the Haute Randonnée Pyrénéenne (HRP) the idea is to walk from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean (or the inverse). But, unlike the French Pyrenean Way (GR10) and the Spanish Senda Pirenaica (GR11), the Haute Route sticks close to the watershed. It strays willfully from France to Spain, sometimes meeting up with the Pyrenean Way, sometimes strolling alongside the Senda.

It would be my third – and last – crossing so:

- I must finish in good shape. The Pyrenean Way defeated me two days before the end. The Senda left my feet in rags. Only after three days in bed could I put them on the ground again and muster the strength to go to the doctor. I want to enjoy not just arrive.

- It has to be done in one summer. The Pyrenean Way took me four; the Senda three. For it to be really satisfying the Haute Route has to be walked all at once. This was clearly impossible, my wife Veronica insisted.

- I want to avoid the Pyrenean Way and the Senda as much as possible.

So the plan became to walk from

- Hendaye to Somport (13 days)

- Somport to Bagnères-de-Luchon (14 days)

- Bagnères-de-Luchon to L’Hospitalet-près-l’Andorre (17 days)

- L’Hospitalet-près-l’Andorre to Banyuls (13 days)

returning home in between. Fifty-seven days, though the guides yomp across in 41-45 days.

Days 1–6 Hendaye to Orreaga/Roncevaux

France

For my first day the Haute Route follows the Pyrenean Way through rolling countryside under a scorching sun.

Spain

I crossed the border at the col d’Ibardin. This area used to be a haunt of smugglers but there is nothing clandestine about the out-of-town top-of-the-hill shopping centre now. My second night was at the little-known hotel at the col de Lizuniaga.

The shooting butts are the second line, behind the traditional palombières. Both await the migration season and the arrival of flocks of wood pigeons heading south. The American film director Orson Welles came here in 1955 to make a documentary for his series “Around the World”. Vintage cinema. As he says, at the traditional palombières: “The birds are netted out of the sky, like fish.” (The sequence on the palombières starts at 2:13). Those which escape are then picked off here.

Theoretically the watershed defines the French/Spanish border but doubts about its exact position and local preferences resulted in disputes. So in the mid-19th century the border was defined by 602 numbered posts, concentrated at the two ends. The middle was no use to anybody and the watershed easy to recognise so posts are much less frequent there.

I wanted to avoid the long day on the standard Haute Route, most of which I had already walked, so I went to Zugarramurdi. This is one of the few areas north of the watershed which are still in Spain.

The village houses a museum to honor the memory of those suspected of witchcraft. After the trail at which many ‘witches’ were condemned to be burnt at the stake a new judge was sent to investigate a fresh wave of accusations. “I have not found one single proof nor even the slightest indication from which to infer that one act of witchcraft has actually taken place,” was his conclusion.

The village also promotes a vast cavern where the sabbaths were said to have taken place. This is a convenient local tradition. There is nothing in the detailed documentation of the Inquisition to link the cavern with the events. (See El abogada de la brujas.)

If my memory serves me well, it is here that the Inquisition lodged.

Going back over the watershed, I met some pilgrims heading for Santiago. Given the increasingly overcrowded main routes, many people are turning to other possibilities. After all, in the Middle Ages one walked from home to Santiago and back again.

I have timed my arrival in Arizkun to coincide with the midsummer eve festivities, which are part of a widespread Pyrenean tradition.

The houses here are designed to last. The rules of inheritance ensured that the first-born would inherit the house and land. This left younger siblings at the mercy of their elder brother or sister unless they married another first-born. However it did ensure the survival of viable agricultural units and encouraged solid architecture.

“Musikarekin askatasuna” translates as “musical freedom” but the artwork is much more political than it seems. The electric guitar evokes banners demanding that condemned terrorists be allowed to serve their sentences in the Basque country.

After Arizkun I headed back to meet one of the Haute Routes in Aldudes.

France

This is an odd valley. Higher up at its head in the Pays Quint, the soil is Spanish but the grass is French. The inhabitants are French, and pay French income tax. But they live permanently in Spain and pay land tax to Spain.

Spain

Orreaga is where some versions of the Haute Route (W–E) and the Chemin de St Jacques (N–S) meet. I had a credencial (pilgrim passport) forced on me though I explained that I wasn’t heading for Santiago. The hotels and restaurants now buzz all year round, though in the 1970s hardly anyone came here.

More to follow.